[Published: The Daily Telegraph]

One day when I was about five, thousands of spiders started spilling from the light above my bed. They were wispy things, but as they fell, arm in arm, they formed a diaphanous curtain that swept over everything – the ceiling, the walls, my skin. They burned with colour, and they hurt me. Just before I went blind – and just after I decided I was probably going mad – the world twisted apart at the seams. And it hurt me. At the seams.

About 8.5 million people suffer from migraine attacks in the UK. Of those, around one in five experience “aura”: a gamut of symptoms that can include everything from vertigo to audio hallucinations. My attacks are preceded by radical mood swings and a hypersensitivity to light. (I have more sunglasses than Bono.) Small phrases repeat in my head.

My memory and sense of time collapse, making it impossible to tell whether an hour or a week has passed since my bedroom door last opened. Small phrases repeat in my head. Soon I develop a stammer and a suffocating confusion. Like a parent picking their child up from the cinema, sentences loop around and around without finding a place to. Eventually, I’m left with the inner life of a parrot: shpaed gibberish, tohhugts fromed out of pure hbait. None of this makes for a terribly good Tinder profile; and it hurts like nothing else on earth.

“If you visualise the brain as being like a cauliflower,” says Dr Giles Elrington, a consultant neurologist and former Medical Director of the National Migraine Centre, “in the stalk of the cauliflower, in the brain’s stem, there is overamplification – normal sensory messages are amplified to the point where they are distressing, causing the pain, nausea and light sensitivity of an attack.”

“Aura is a very different matter – it’s a wave of suppression of function in the cortex of the brain, in the florets of the cauliflower.”

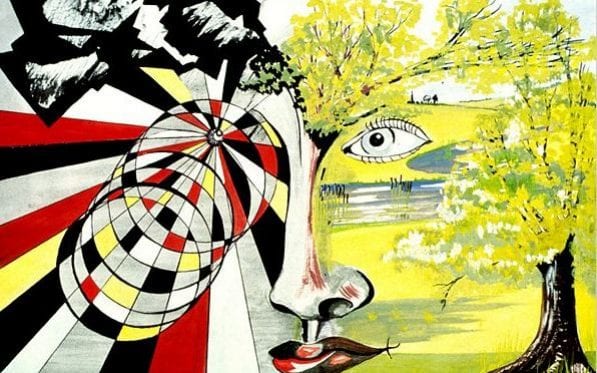

Essentially while one section of your brain is on fire, there is a rolling blackout across the rest. But it’s what this can do to your vision that can be most debilitating. Huge blocks of prismatic colour are separated by jagged lines of non-colour, a crack in your vision, seams. Sometimes these lines are great livid girders, the Forth Bridge being sucked into a black hole. Sometimes they’re thin, like the craquelure in an old painting. For me the effect then multiplies until I’m blind, trapped in a stained glass window. It gets quite gothic.

Speaking of: Hildegard of Bingen was a 12th Century abbess famous for her religious visions. In illustrations produced at the time, swirling stars fall over geometrics landscapes. God’s kingdom burns with colour.

Hildegard and her visions form the start of Migraine Art, the definitive book on aura by Dr Klaus Podoll and Derek Robinson. Based on paintings by migraineurs, it splits visual aura into a number of exciting genres: the likes of scintillating scotoma (stars), fortification (zig-zags like a castle wall) and allesthesia (images transposed between eyes).

More examples are available at the Migraine Art collection and in amateur animations on YouTube, and it’s all instantly recognisable to a sufferer. Like Richard Dreyfuss making mountains out of mashed potato, we’re clearly all receiving the same signal.

These phantasmagoric hallucinations have also inspired professional artists. Discussion rages as to whether Van Gogh and Picasso painted from their aura. Georgia O’Keefe drew the forbidding lines of her headaches, reasoning “why not do something with it?” Giorgio de Chirico, a forerunner to surrealism, features people standing around in dream landscapes wearing what look like sunglasses. English artist Sarah Raphael, riven by migraine until her early death in 2001, moved progressively away from portraits to abstraction. Her ‘Strip’ paintings feature the bright colours and dark frames of a comic book colliding in timeless space.

“You can talk and talk, but sometimes it’s easier just to go ‘this is what I see’,” says Fran Kelly, an artist and migraineur. “Communicating migraine through art is quite an effective tool.”

Kelly is never without some kind of aura, ranging from loss of vision to food tasting rotten to a pervasive smell of bananas. Her training as a prop maker led her to create Maison Migraine – an installation that let people experience migraine for themselves.

“I took the most common sensory experiences and then created this room that altered people’s senses,” she says. “So the floor was altered, we had unreadable magazines, smells, a soundscape, everything.”

It’s a cross between a lounge and my own personal Room 101, but until you picked up a magazine or popped a foul tasting sweet into your mouth, you might not have realised anything was wrong. “Taking pictures, I wanted it to look normal, because I wanted people to feel familiar,” says Kelly. “They could be sat at home and then all of a sudden this weird thing starts happening to them.”

This breakdown in reality is a common obsession for writers with migraine. Lewis Carroll inspired a whole symptom. ‘Alice in Wonderland syndrome’ is the sensation that you or your surroundings are too big or too small. Emily Dickinson wrote about the “funeral in her brain” where “a plank in reason, broke, and I dropped down, and down”. Three times as many women as men suffer migraine, and for Virginia Woolf the dismissiveness around ‘women’s illness’ compounded the limits of language itself: sufferers are forced to take their “pain in one hand and a lump of pure sound in the other.”

Of course, describing the indescribable is one definition of art. “I think unless you’ve had a migraine, you really don’t understand what they’re like,” says Sinéad Morrissey, winner of the T.S Eliot and Forward Prizes for poetry. She has written movingly on the onset of an attack: lines like “vandals set loose in the tapestry room” and “I have given up all hope for what was whole” are profoundly affecting for sufferers.

“I’ve written two poems called Migraine,” she explains. “It’s something I come back to, to try to do it justice in some way. They can be so extreme as an experience, and they mess up your basic cognitive functions so much, it’s a challenge to try and convey what that’s actually like in language.”

“I still haven’t fathomed the range it presents,” agrees Hilary Mantel, the Booker Prize winning author of Wolf Hall. “Musical ear worms, or a banal phrase repeating in my head till it becomes charged with meaning, like a spell. A prolonged and dislocating sense of deja-vu. Sensory memories welling up from a deep place.”

After first being diagnosed aged 18, her headaches have now largely worn off. However, the aura remains, and she recognises this can be a blessing as well as a curse for an artist.

“Sometimes I get savagely impatient with prolonged aura, but sometimes it leaves me a gift – a breakthrough, a sudden insight – something I can use.”

“If I can manage to write, I get an excellent payoff. But it’s a rough way to work. I feel haunted by myself – it’s as if there are two realities, slightly overlapping, and around them a nebulous, faintly illuminated area like spun fog – so I don’t feel securely based in my body; my personhood is adrift, and so is the division between past and present.”

Morrissey can also see the benefits of aura, but there are dangers too.

“Perhaps some degree of synaesthesia is involved, which is always a rich seam for art. On the other hand, even talking about them can make me feel ill, scared that I’ll somehow conjure one just by thinking about it.”

It’s a problem that has shaped Debbie Ayles’ career as a painter. Her earlier work is difficult for me to look at: electric colours over harsh patterns, heavily inspired by modern architecture. Somehow, they remind me of my aversion to venetian blinds.

“Unconsciously in my paintings I was placing colours and tones such that they ‘twinkled’,” she explains. This ‘twinkling’ was her aura, but she had no idea. “I discovered via Klaus [Poddoll] that this was triggering basilar migraine. Initially I was totally unaware of what I was doing.”

Since this realisation her art has eliminated the dangerous colour variations and patterns, working towards a “post migraine” style.

“I had to think about how to keep to my inspiration and my particular style whilst not causing me (or any audience) any pain. If anything, I guess I’m a post migraine survivor artist!”

She has since written on other artists and migraines, including Sarah Raphael, and has learnt how to recognise migraine sufferers from their art. Working with Professor Arnold Wilkins at the University of Essex, she also developed guidelines for “safe” public art for use by councils and public bodies.

Ayles’ methods, along with news of a possible treatment involving antibodies in the brain, suggest there is hope. But even beyond the aura, attacks and “postdrome” hangover, migraines have an affect on your outlook. The overriding feeling of migraine art – whether it’s Maison Migraine or Alice in Wonderland– is that our experience of life is a negotiation that can break down.

Those endless fractal patterns suggest a fractured reality. It’s like leaning your head up against the TV and seeing the dots, or the movie slowing down until you can see the gaps between the frames. I have grown to fundamentally distrust the world: to suspect that at any moment, it will twist apart again.

“Migraines knock you out of your life,” says Morrissey. “You know a fixed reality is contingent upon the blood vessels inside your brain not contracting suddenly, of their own accord, and then filling your head with blood.”

“Sometimes it’s like looking into the abyss – they have suffused the tone of my world with something mystifying and unpleasant,” says Mantel. “The smashed glass you get after a fire, darkened with smoke – that’s my window and my mirror too.”