Ask any Scottish person who lives in England, or has been to England, or has ever met an English person, and they’ll tell you about ‘the look’: people smiling at you with a knitted brow, nodding but baffled. It’s the look people get when they have no idea what you’re saying, no matter how often you repeat it. Sometimes they pat you on the arm, conciliatory, in case you’re trying to start a fight.

Meanwhile, you’re still lost and don’t know how to get to King’s Cross Station.

The tech industry is banking on artificial intelligence like Siri, Alexa and OK Google becoming ubiquitous – soon speaking to your computer, phone and smart home will be second nature. Like any nerd who grew up on Star Trek: The Next Generation, I’ve been waiting for this my entire life. I remember reading out chunks of Bill Gate’s autobiography to train early versions of Windows speech recognition. (It didn’t work.)

The technology has improved immensely since then, but there’s still a problem: me. Personally I quite like my voice – a mix of Edinburgh vowels and Glaswegian pace, with big Rs to match my big arse. (It’s why we wear kilts.) But like Londoners and YouTube commenters before them, the robots tend to respond with a blank look.

I have Amazon’s Alexa in every room, but the shopping lists she writes are baffling haiku, leaving me to ponder “ride the wind chaff” while standing in the cereal aisle. Every time Siri responds to a long question with a non sequitur like “Hello Jonathan,” I imagine her smoothing my hair – Fay Wray to my King Kong, trying to calm my unintelligible grunting.

And I still don’t know how to get to King’s Cross.

Like every other Scot I know, this forces me into vocal callisthenics in an attempt to be understood: tuning vowels like a Theremin, dropping consonants, picking them up again, and eventually doing an imitation of the cast of Downton Abbey.

So what happens when these systems are everywhere? Skynet has no problems chatting with Arnold Schwarzenegger, but what about me? What will it mean for the Scottish dialect when half of our conversations are with robots, and everyday life depends on being understood?

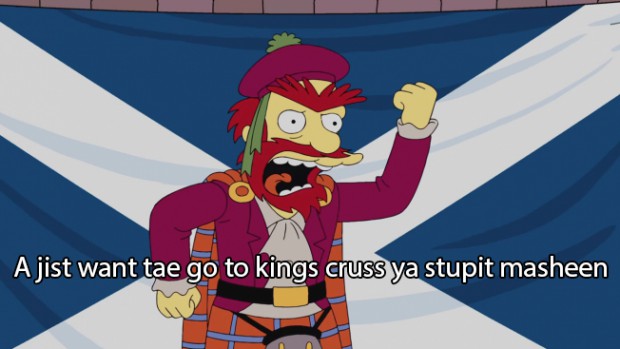

It’s a problem that was perfectly summed up by comedians Iain Connell and Robert Florence in the sketch show Burnistoun.

Ironically the machines might not understand Scots, but they do sound like us. Gillian Hay is an actress from Ayr, birthplace of Robert Burns. She’s lent her voice to major multinational companies and her accent – a West Coast “flexible register” that, according to her CV, can become “instructional, sexy or smooth”– makes me want to burst into tears and board the next train home. If you’ve ever been put on hold, there’s a reasonable chance Hay is on the other end of the line.

“I get texts from my family going ‘you’re really annoying’. I think they find it more surreal than I do.”

Surprisingly, she considers her accent a major plus in her line of work. “It’s so light and conversational. In the last few years a lot of companies have started using Scottish female voice overs, especially financial companies.”

(Please, save your jokes.)

Hay points to surveys in which the Scottish accent is regularly voted the most friendly and trustworthy in the UK. But some allowances have to be made.

“The Scottish accent can be quite staccato, especially on the West Coast, the vowels are shorter and the consonants are sharper. I’ll elongate the vowels and I’d never do a glottal stop: when you don’t pronounce the ‘t’ in words like bottle or butter. But if I’ve just been home, where everyone is bo’ling and bu’ring away…”

So, the crucial question: even with her honed, controlled voice, do the machines struggle to understand her? She starts laughing.

“Yes! I find these systems don’t recognise my accent, even though I do them, which I find hysterical. You have to speak in an English accent, don’t you? I remember trying to book cinema tickets, and I’d always end up going [drops into Maggie Smith impression] “Burns Statue, Odeon, Ayr”. And then it would just cut you off!”

She’s quick to add: “Luckily the ones I voice do understand me.”

Well you’d hope so.

It is hard to know if Scots are genuinely less understood than other English speakers – none of the main companies could provide someone to talk to about the issue. And while you might trust us with your pension, another study showed Scots are the most likely to think we are being discriminated against due to our accent. Siri could be hitting the same nerve that gets me into fights at Wetherspoons.

Then again, it’s not paranoia if it’s true. The man who literally wrote the English dictionary, Samuel Johnson, was a notorious Scotophobe. Regardless, even the perception that some voices are better understood than others speaks to bigger issues, and could have big consequences.

“I think it’s incredibly important,” Hay says. “These systems should be made to recognise everybody, from Wales to Stornoway. When I’m recording, some people will say ‘you’re saying that word wrong’, but it’s correct in my dialect. I come from Ayr, where Burns was born, and Auld Lang Syne is sung all over the world at New Year. So who’s wrong, who gets to decide that?”

It’s a good question, and brings to mind the last time technology collided with British regional accents: BBC pronunciation.

“BBC pronunciation was, in the 1920s and 30s, a side effect of the new technology of radio,” Dr Jürg Schwyter explains. “You mustn’t forget that the microphones and broadcasting over the ether was full of white noise, crackling, and so on. So the announcers and newsreaders where really a cast, ‘for which specific training was required,’ in the words of Lord Reith. This training consisted not only of ‘good English’ but also of how to speak before the microphone.”

Dr Schwyter is the author of Dictating to the Mob, a fascinating history of the ‘BBC Advisory Committee on Spoken English’. This body defined the voice of the radio age – setting down rules of speech and pronunciation for the first generation of presenters. Writing in the Radio Times –then the official organ of the corporation– Honorary Secretary A. Lloyd James compared speech to “railway gauges, the pitch of screw threads and the pitch of musical notes.”

“Standardisation is the antidote to chaos,” he argued. “Increased communication means an increase in standardising the means of communication.”

‘Received pronunciation’ became that standard, despite the fact that the first Director General of the BBC was Scottish. RP is interesting because it’s associated with class rather than geography – posh people come from everywhere, with the accent regulated at schools and universities. In some ways, it was the perfect basis for the insubstantial ‘voice of the air’, which comes from nowhere and everywhere at once.

BBC English not only helped reinforce RP as the language of prestige and intellect, but led some campaigners to worry it discouraged variation among listeners. ‘Proper’ pronunciations of words were even published in Radio Times next to the programme times, so people could learn to speak good while planning their evening’s entertainment.

This eventually led to a backlash, with a push for more representation of regional accents on screen. However, Schwyter points out that it wasn’t exactly a full-blown revolution and Scots were luckier than some.

“Yes there was a backlash,” he explains, “mostly not of traditional dialects, but of social ones. Cockney, for example, was heavily stigmatised and could be heard on the radio only in comedy programmes.”

In fact, Schwyter says, by the committee’s standards “the ideal speaker would probably be ‘an educated Scot’ as ‘she or he follows the principles automatically.’ The keyword is educated. The BBC of the 1920s and 30s remained a frightfully snobbish and upper-class institution.”

“I do not think that technology alone can influence the way we speak,” he goes on, “except for a few self-conscious corrections, sometimes hypercorrections, in formal styles. It is much more the personal contact that is needed for a feature to feed through language.”

It’s worth noting that while there is much work left to do, many regional accents now appear on the air. I actually worked at the Radio Times until recently, accent and all. When I left they gave me a picture of Groundskeeper Willie as a farewell present.

But what about this new breed of talking machines? Could ‘robot pronunciation’ replace RP? Is Alexa now a digital Henry Higgins, constantly correcting and chiding our grubby little dialects?

“Had there been no technological progress, robot pronunciation might have become the new RP of the 21st century,” Schwyter allows. “But now, I think, technology has made such enormous and rapid progress that this is no longer the case. I’m not sure that in 2016 it’s still the case that certain accents are favoured over others.”

This question of how far the technology has come is a crucial one – whether the software will improve fast enough to adapt to Scots, or whether Scots will adapt to it. But neither will help if it doesn’t speak our language at all.

Many don’t realise Scots is its own recognised language – distinct from mere English with a Scottish accent– even if they use certain words everyday. Wee, braw, dour and numpty are not slang from the Urban Dictionary, they’re drawn from a pedigree every bit as impressive as the language of Shakespeare. Yet call Siri stupid and she’ll get offended. Call her glaekit, and she’ll smile and nod uncomprehendingly.

“This is a thing that stretches back into the centuries and helps us shape our identity,” says Michael Hance, Director of the Scots Language Centre, “and it doesn’t have any of the recognition that a historic house or castle might have.”

The Scots Language Centre promotes the language both in politics and online, publishing across countless social media platforms to encourage its use into the 21st Century.

“People have the right to use the language that is native to them,” he argues, whether it’s in conversation, online or with their smart fridge. “It’s about respect for linguistic diversity, recognising that the speakers of this language are entitled to be treated with respect.”

Thus far, none of the main voice control systems use Scots as a language. While the Scottish Government’s official ‘Scots Language Policy’ is to “promote the acquisition, use and development of Scots”, I got no response to questions for this article. Hance is concerned that the Burnistoun sketch may come true, and that if the machines we talk to don’t use Scots words, neither will the Scots.

“It’s a common experience that everyone in Scotland will have had: how do I say this so the technology will understand? And you change the way you speak. It’s not even subconscious, you have to put thought into it.”

“What will this do to the way people speak? I think it’s an absolutely valid question. For years I’ve been thinking, is this going to be the straw that broke the camel’s back as far as this language is concerned?”

However, like Schwyter, Hance believes there is hope as long as the technology keeps pace with the Scots tongue.

“Yes it has the potential to alter the way people speak, but if the technology can be made more responsive to users, then it’s possible we won’t have this problem.”

Indeed, it’s important to remember that for all the grousing, computers have been a boon to language and communication. Dr Schwyter is now reliant on dictation software, following a stroke years ago.

“Imagine, if I had had the stroke in the 1950s,” he says. “I would be out of a job and the BBC book – which I dictated with Dragon Dictation — would never have been written. Honestly, it’s close to a miracle.”

For Scots too, the Internet has provided arguably the first real chance to express their native tongue outwith the traditional, disapproving publisher model. Fans of the hilarious genre Scottish Twitter know this well.

“The Internet has given people a huge amount of freedom to express themselves, in ways which previously they didn’t have,” Hance says. “The space itself is actually quite liberating for Scots speakers, because they find a place where there isn’t the same degree of censorship that there was before.”

(Oh, and in case you’re about to comment, ‘outwith’ is a word from Scottish Standard English. I once had a stramash with a sub-editor about this.)

Everyone remembers Robert Burns and his “wee, sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie”, but they forget the focus of that poem isn’t the mouse, but the man who ploughed through its burrow – he was too wrapped up in his own progress to see he was accidentally causing harm. The best laid plans of mice and men, and aw’ that.

No one is expecting Siri to speak in brogue, or Alexa to address the Haggis or tell jokes like Billy Connolly. The point is that languages are living things, sustained and nurtured by the people who speak them. Once the machines join that conversation, they share in that responsibility.

Ye ken?